Broad Fellows Research Statement

by Eric J. Ma (MIT)

RESEARCH BACKGROUND: My research background, which has included both experimental and computational components, has provided me with an excellent set of tools with which to tackle this problem. My experimental training was in synthetic biology, where I spearheaded the formation of the 2009 UBC iGEM team. We built an analog threshold sensor in E. coli (named the "Traffic Light Sensor"), winning a Gold medal standing with the team in our first year of competing. My contributions included sourcing $6000 in student stipends, $500 in DNA synthesis sponsorship, and aiding in securing $10,000 from the UBC Teaching and Learning Enhancement Fund for the following competition year, and co-delivering our final presentation at the 2009 iGEM Jamboree. I also served as an advisor to the 2010 UBC and 2011 UCSF iGEM teams.

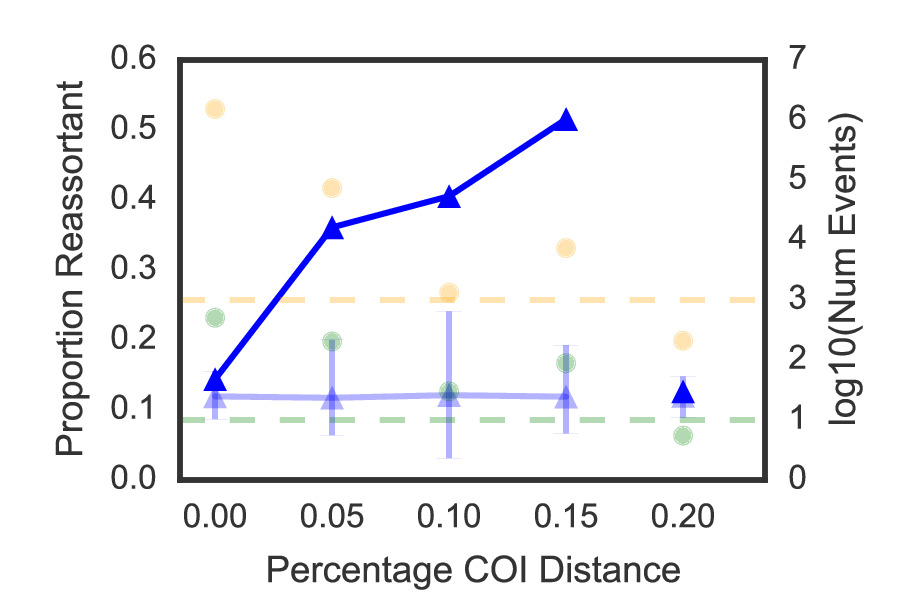

I moved on to apply computational approaches to the study of influenza ecology and evolution under Prof. Jonathan A. Runstadler at MIT. My first area of focus has been on influenza disease ecology. Together with my colleagues in the Runstadler lab, we have investigated the role of reticulate evolutionary processes in influenza virus host switching and seasonal persistence (1, 2), and I have won poster presentation awards (CEHS 2014, Broad Retreat 2015) based on this work. I developed a heuristic algorithm that enabled us to (1) identify reticulate evolutionary events at scale while accurately approximating phylogenetic relationships, and (2) quantitatively measure the importance of reticulate evolutionary processes in ecological niche switches (Figure 1).

The second (and more recent) focus is on the prediction of viral phenotype from genotype, otherwise known as phenotypic interpretation of genomic data. This is where my current efforts are focused, enabled through collaborations with Profs. David Duvenaud (U Toronto) and Paul Blainey (MIT/Broad Institute), and through the Broad Next10 program. My colleagues and I have observed that single point mutations in a viral protein are sometimes necessary but not always sufficient for accurately predicting quantitative protein phenotypes. Additionally, epistatic interactions within a protein complicate the phenotypic interpretation of genomes, limiting the usefulness of identifying single point mutations. To solve this problem, we have identified the following needs:

- Systematically measured paired genotype-phenotype data with modelled uncertainty in measurements.

- Machine learning algorithms capable of predicting quantitative phenotype from the 3D models of a protein with associated uncertainty.

A key contribution that we expect to emerge from this work is a gold-standard template for predicting viral risk from sequence; this area of focus is the centrepiece of this Broad Fellows application.

Apart from these two main areas of focus, I have also collaborated with colleagues in the use of Bayesian phylogenetic methods to study influenza movement and reassortment in wild animals (3, 4), and performing statistical analysis methods of viral phenotype data (5, 6).

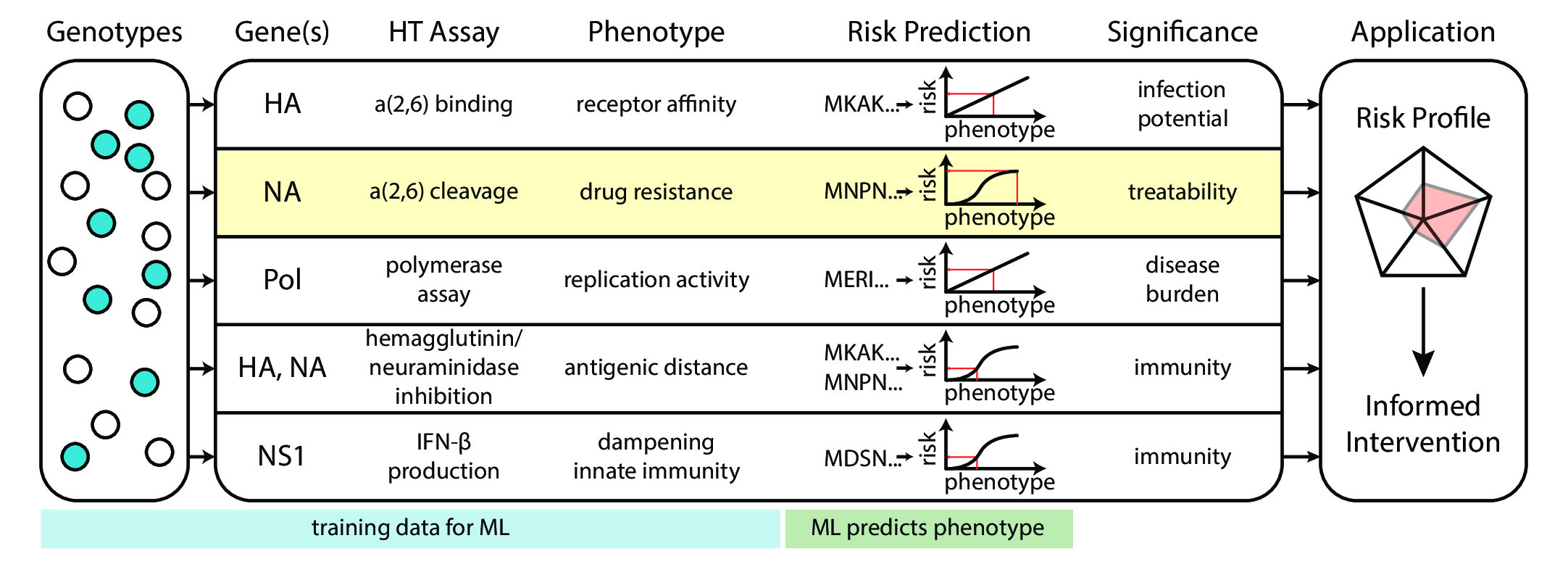

BROAD FELLOWS VISION: As a Broad Fellow, I envision building the necessary experimental and computational systems for making phenotypic interpretation of viral genomic data a timely, rational and predictive endeavour (Figure 2).

A goal of viral genomic surveillance is to help guide appropriate interventions, given sequence data. Risk determination is a necessary step. Health risk is partially determined by a host's response to infection, and partially determined by a virus' biochemical phenotypes. Virus biochemistry is, in turn, determined by its proteins' sequence. While there are numerous studies describing the biochemical and physiological characterization of virus mutants, rational risk determination based on sequence remains elusive, and experiments with conflicting effects cannot be easily compared, because of non-standardized controls, protocols, and measurement metrics. As a field, genomic surveillance groups lack the capability to accurately predict phenotype from genotype (7). At its essence, I see this phenotypic interpretation issue as essentially a machine learning problem that lacks data. To solve this problem, my goals are two-fold:

- To be able to rapidly phenotype a virus while minimizing experimentation on its live form, and

- Develop interpretable machine learning algorithms that predict phenotype from protein structure.

With my team, I envision building a real-time phenotype interpretation and risk determination dashboard for viral genomes, backed by experimental data, powered by deep learning, yet user-friendly for use by epidemiologists, physicians and policy-makers alike. In pursuit of these goals, I plan to develop 2 main project thrusts, which I will elaborate on below.

Project Thrust 1: Develop scalable, safe and standardized assays for phenotyping viruses.

Core problems: I believe that the next frontier in real-time pathogen surveillance is to deduce the risk profile of a virus from its sequence. Doing so can help rationally guide medical and epidemiological decision-making in the event of new outbreaks. It is possible now to sequence a new pathogen within 24 hours of isolation (8), and the technology enabling this is being rapidly improved (8–12). Yet, studies that use sequence data tend to be limited to mapping the transmission and evolutionary dynamics of the virus (13–15), and shy away from making phenotypic predictions (7). The state-of-the-art in phenotypic interpretation remains limited to the identification of single amino acid substitutions that are experimentally correlated with (on an ad-hoc basis) some "risky" phenotype (e.g. influenza polymerase replication rate (6, 16–18) and neuraminidase drug resistance (19)).

Phenotypic interpretation tends to be limited to the identification of "famous mutations". For example, E627K in the influenza PB2 protein has been described as being an attenuator (17) and activator (6) of replication and pathogenicity, depending on the background genotype and experiment. Moreover, the absence of E627K can be compensated by mutations at other amino acid positions (16). This example indicates that point mutations are neither necessary nor sufficient for causing a "risky" phenotype; we need a broader view of the data that takes into account all known epistatic interactions, and systematic and standardized phenotype measurements, matched to all known viral protein genotypes, will enable us to get there.

Proposed work: In the first project thrust, my team will systematically measure influenza virus protein variants and their epidemiologically-relevant phenotypes. We will begin with the influenza neuraminidase, which has the signatures of low-hanging fruit:

- It has an epidemiologically-relevant phenotype (drug resistance).

- The phenotype can be measured with an established biochemical assay (20).

- The assay is simple enough to be amenable to robotic liquid handling.

- The phenotype has yet to be systematically measured.

In order to generate protein variant libraries, we will use a two-pronged approach. To learn from historical data, we will use DNA assembly and synthesis methods to create a rational library of existing neuraminidase variants in the Influenza Research Database. To pre-emptively explore genotypic space, we will generate random mutants from contemporary neuraminidase variants that have been sampled in the past year, and sequence the variants that exhibit large changes in neuraminidase resistance.

We will also characterize the influenza polymerase RNA replication rate using a luciferase-based assay. The polymerase replication rate is directly related to viral load, and has been implicated in pathogenic phenotypes; it also fulfills the same four criteria outlined for neuraminidase drug resistance. With colleagues in the Blainey lab, we are also currently exploring alternative assays for polymerase replication that can be conducted at a fraction of the cost, funded by the Broad Next10.

As a "stretch goal" within the Broad Fellows timeframe, with my team I will explore the feasibility of leveraging the influenza virus' genetic systems to develop mammalian systems for continuous evolution, inspired by PACE (21). This may allow us to pre-emptively explore the influenza genotype space faster than manual random mutagenesis, and may also be leveraged as a tool for evolution of proteins that require mammalian cellular modifications to be functional.

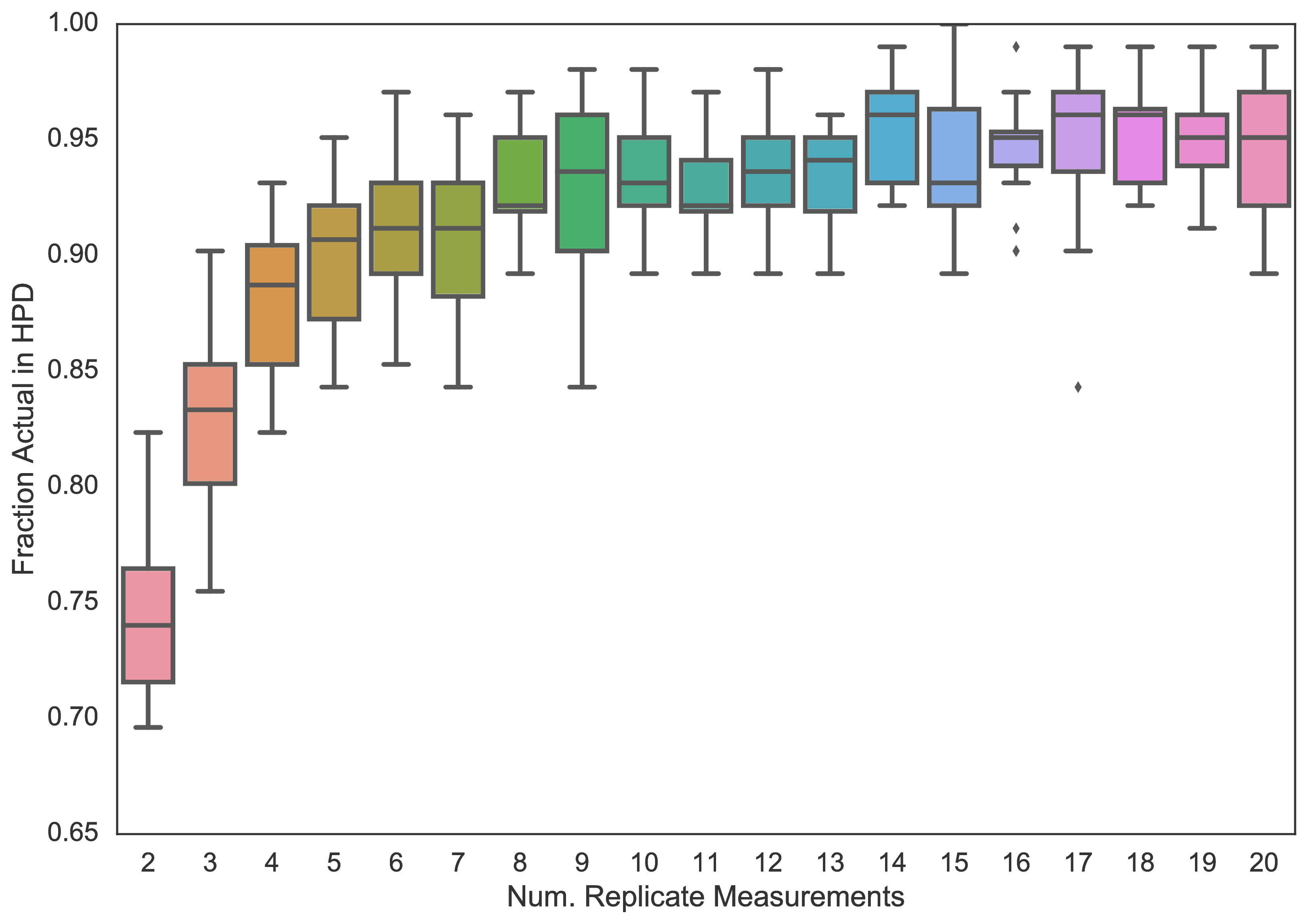

One fundamental problem any research group dealing with high throughput measurement will face is determining the number of replicate measurements that are required. In preliminary work supported through the Broad Next10, I have developed a simple Bayesian statistical framework for analyzing high throughput data, and used it with statistical simulations to empirically determine that 5-6 replicate measurements are necessary for balancing cost with accurate phenotyping (Figure 3). This work, in which a draft version is available as a pre-print on BioRxiv (22), has informed the design of existing assays in our group. We will use this framework with the experimentally measured neuraminidase resistance data to model the uncertainty associated with the measurements, transparently report them as the posterior distribution of credible neuraminidase values given the measurement data, and leverage them in the machine learning models developed in Aim 2.

Concurrent with ongoing systematic testing of the influenza polymerase, I will explore developing high throughput versions of assays to test other viruses. (Whether we are able to modify existing genetic systems or require completely novel ones will require experimentation.) In doing so, I aim to develop a modular, plug-and-play phenotyping system for rapidly phenotyping emerging viral outbreaks as they occur. In the long run, the goal is to develop a toolkit of standardized and scaled phenotyping assays for multiple phenotypes across multiple viruses.

The data that my team will generate will have advantages that stand in contrast to the current available data. Firstly, it will be data relevant to understanding the mechanistic underpinnings of influenza risk and pathogenesis. This stands in contrast to more easily collectable proxies, such as the number of influenza-like illnesses (ILI) per year and viral load in patient cohorts, both of which are far removed from pathogenesis mechanisms. Understanding the biochemical underpinnings of pathogenesis also opens opportunities for the development of drug treatments. Secondly, the data will be standardized, allowing for easier inter-comparison between genotypes. This stands in contrast to the currently available phenotyping data, which are measured ad-hoc and difficult to compare because of the use of non-standard baseline controls. Finally, unlike current gold standard datasets (e.g. the HIV drug resistance database, which reports single values per genotype), by explicitly reporting uncertainty we will improve scientific transparency, and including them in machine learning applications will allow for propagation of uncertainty to final predictions.

Collaborations: I anticipate partnering with the Chemical Biology and Genomics Platforms to accelerate the experiments described above. Additionally, I will continue to collaborate with colleagues in the Blainey lab, and explore collaborations with groups affiliated with the Infectious Disease and Microbiome Program, such as the Sabeti lab.

Short-term milestones: In the spirit and interest of open science, the protocols and data generated will be released freely through a web interface hosted on the Broad Institute, available for the research community through a web-based interface, and publicized via open access publications (e.g. in Scientific Data, a Nature Publishing Group journal). All derivative publications will be deposited on pre-print servers (BioRxiv) and published in open-access venues.

Project Thrust 2: Develop and deploy machine learning models that predict quantitative biochemical phenotype from structure.

Core problems: Given the complex amino-acid interactions that give rise to a protein's biochemistry, I believe that machine learning is the key to interpretably map genotype to phenotype. While machine learning algorithms have been used to predict protein properties from sequence (23–28), as of now, current algorithms are:

- Unable to accept variable length sequences as inputs

- Require the inference of epistasis rather than explicitly accepting it as part of the input, and

- Lack the capability to produce uncertainty estimates for new predictions.

These hinder progress towards a rational evaluation of a virus' risk for the following reasons.

Variable length inputs are a problem because virus proteins can undergo insertions and deletions as part of their evolutionary trajectory. Yet, machine learning algorithms require fixed-length vectors as inputs. Interpolation is a proposed solution (29), but it distorts the original protein information; multiple sequence alignments do not fundamentally solve this problem either, as a new alignment needs to be produced when a new protein sequence of a new length arises. Circumventing these problems will allow us build streamlined pipelines for general purpose machine learning on proteins.

Additionally, proteins fold into complex, 3-dimensional structures, dictated by amino acid interactions. Machine learning with linear protein sequences necessarily requires that the interactions be inferred. Yet, where the crystal structure of a protein already exists, and homology models can be constructed, inferring interactions is unnecessary and may even be inaccurate. Designing a machine learning algorithm that explicitly learns from the 3D protein structure will allow us to interpretably infer the biochemical interactions responsible for phenotypes, and move beyond single point mutations to biochemical characteristics underpinning phenotypic changes (e.g. "flipping from a positively to negatively charged patch").

Finally, current algorithms have no notion of uncertainty in the predictions, producing only point estimates. This can pose a problem for decision-makers. Suppose for a circulating virus population predicted drug resistance lay below some threshold, permitting the deployment of drug for treatment, but the uncertainty was large enough that it could have well been, in reality, a resistant virus. In this case, if we knew that the uncertainty was large, we would likely have triaged the virus for deeper experimental phenotyping to confirm its phenotype, rather than risk the further spread of a drug resistant virus.

Proposed work: As a Broad Fellow, I will leverage my mastery of probabilistic programming to develop, with collaborators, a Bayesian deep learning algorithm for use with our influenza phenotyping data. This deep learning algorithm will accept variable-length inputs, and produce uncertainty estimates in predicted values, thereby allowing us to rationally monitor an outbreak in real-time, thereby solving the problems outlined above.

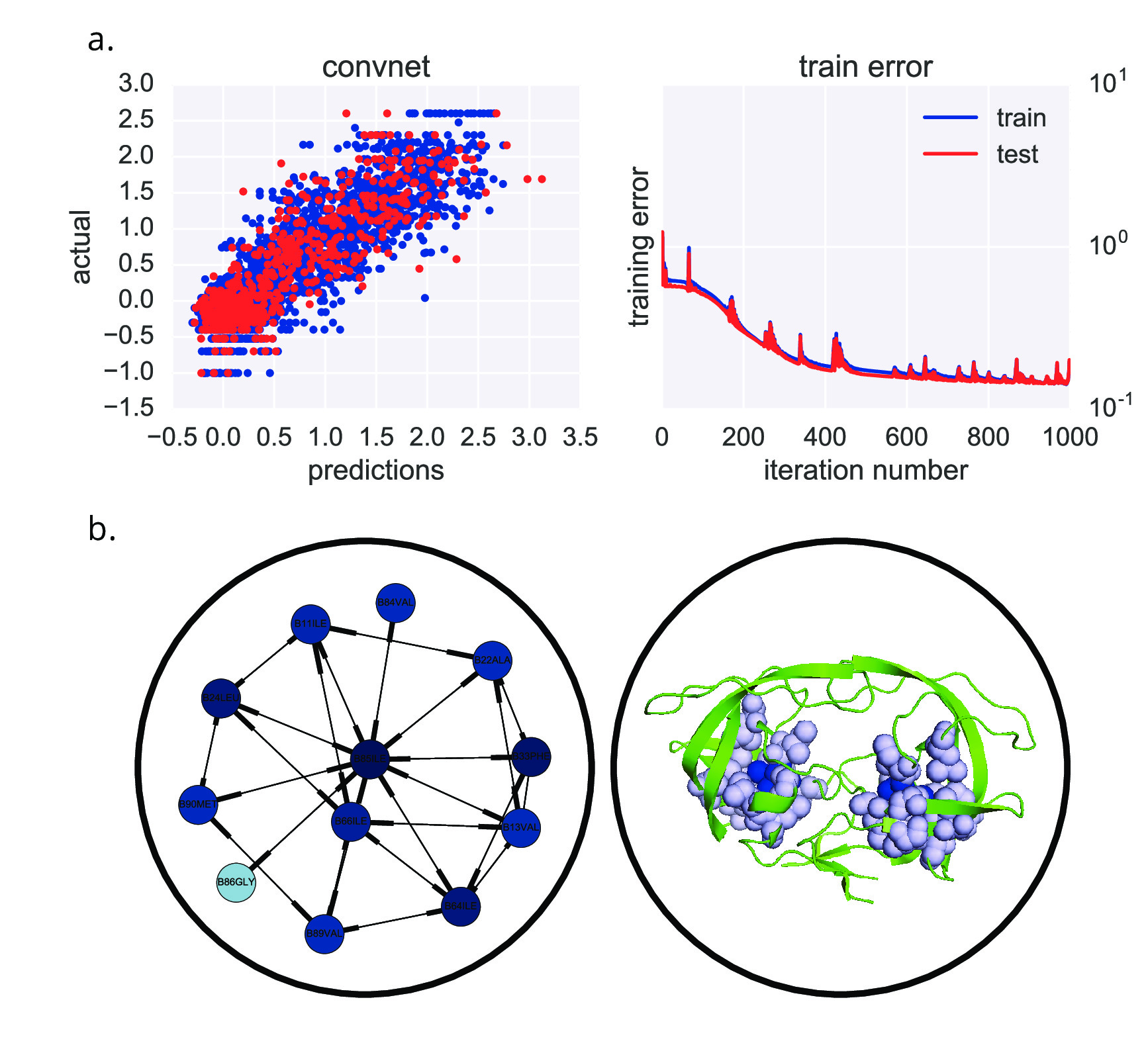

As groundwork for this, I have been collaborating with Prof. David Duvenaud (Univ. Toronto). He has developed a convolutional neural network for learning properties of small molecules, such as solubility and cellular toxicity. I have extended this to protein structures, and have been developing software packages to accomplish this. In a proof-of-principle, I have successfully trained an alpha version of this neural network on HIV-1 protease drug resistance to fosamprenavir (FPV), and used it to identify known amino acids clusters that are positively or negatively associated with FPV resistance (Figure 4).

As the current implementation produces point estimate predictions without quantifying uncertainty, I will use probabilistic programming to implement a Bayesian version of the algorithm. This will allow us to propagate the uncertainty associated with systematic measurements (from Aim 1) to uncertainty in neuraminidase drug resistance predictions. This quantified uncertainty is also the precision in our prediction; knowing which genotypes have greater uncertainty can help with triaging genotypes for further phenotypic testing.

Following this, I will use data generated from Aim 1 as training data for the deep learning models developed here in Aim 2, and use this to generate global and historical predictions of influenza drug resistance. Once paired with multiple other phenotypes, we will gain the capacity to quantitatively map the risk profile of newly emerged viruses.

Collaborations: I will continue to collaborate with David as he continues his tenure as a new faculty member at the University of Toronto. Additionally, I expect that this project thrust will open up new computational avenues for Broadies to leverage, either in the form of workshops on machine learning or through research collaborations.

Short-term milestones: My team will release the protein interaction network and graph fingerprinting software alongside manuscripts in open access publication avenues. All of the software will be freely available and archived in long-term repositories (e.g. Zenodo) in accordance with open science principles.

FORECASTED IMPACT: Viral infectious agents cause loss of life, productivity, and health, and as a research field, we are only recently building the capacity to genetically monitor viral outbreaks in real-time. My projects are geared towards making real-time phenotypic monitoring a reality. With the research program that I am proposing, I foresee multiple levels of impact, described below.

Societal Impact: My vision is to build a real-time dashboard for epidemiologists and policymakers. This dashboard will be powered by deep learning models, capable of producing accurate and precise estimates of a virus' risk as soon as it is sequenced. I also aim to develop the proposed phenotyping platform to be ready for experimentally determining the phenotype of newly emerged viruses (especially those which have large uncertainty in their predictions) in real-time. These actionable data will enable epidemiologists and policy-makers to execute data-informed interventions.

Industrial Impact: In order to pre-emptively identify viral proteins that exhibit resistance to newly developed drugs, we can create new synthetic protein variants using contemporary strains as the starting sequence. Medicinal chemists may be able to leverage the phenotyping platform to pre-emptively test new versions of their drugs and validate their effects.

Scientific Impact: By using predictions from our trained deep learning models, we may re-examine historical trends of neuraminidase drug resistance over time, possibly providing greater resolution when compared against the use of H275Y and I223V molecular markers of resistance. We may also combine our predictions with Bayesian phylogenetic modelling to better understand how public health interventions affect the phenotypic evolution of viral pathogens. This will further our basic understanding of pathogen evolution. This is a low-hanging fruit which I hope to pursue as soon as we have the data available.

Broad Community Impact: With the proposed scalable assays developed, I foresee collaborating with other groups at the Broad who are interested in drug repurposing efforts. For example, with our proposed phenotyping system, we may be able to identify combinations of existing non-toxic molecules that target multiple components of flu simultaneously, reducing the likelihood of viral drug resistance. Moreover, our algorithm efforts and data sharing practices may open avenues for collaboration with the Data Science and Data Engineering Initiative at the Broad.

PLANNED FUNDING AVENUES: In order to sustain this work beyond the Broad Fellows period, I will solicit funding from a variety of government and philanthropic sources. The Broad Next10 program is already supporting this work through two grants totalling $80,000. Apart from the NIH R21 proposal that I wrote with my advisor Jon and collaborator David, I foresee this being of interest to the DARPA Prophecy program, the Gates foundation, NIAID, and companies interested in drug development. To acquire a continued revenue stream for the research and development work, I will explore the use of funding models through application programming interfaces (APIs) that allow access to value-added data and models, which may be of interest to other academic and commercial entities (30, 31).

CONCLUSION: My long-term goal is to make surveillance a holistic and rationally predictive endeavour, and that necessitates open participation by and access for the surveillance community. My team will use a mix of high throughput experimentation with Bayesian deep learning to achieve this. We will publicly release this systematically measured pathogen phenotype data (i.e. "The Broad Viral Phenotype Collection"), with a view towards positively impacting pathogen genomic surveillance efforts and setting the standard for rational phenotypic interpretation.

The full version-controlled history of this research statement can be found online.

References

1. Ma EJ, Hill NJ, Zabilansky J, Yuan K, Runstadler JA (2016) Reticulate evolution is favored in influenza niche switching. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 113(19):201522921–5339.

2. Hill NJ, et al. (2016) Transmission of influenza reflects seasonality of wild birds across the annual cycle. Ecology letters 19(8):915–925.

3. Bahl J, et al. (2016) Ecosystem Interactions Underlie the Spread of Avian Influenza A Viruses with Pandemic Potential. PLoS Pathogens 12(5):e1005620.

4. Bui VN, et al. (2015) Genetic characterization of a rare H12N3 avian influenza virus isolated from a green-winged teal in Japan. Virus genes 50(2):1–5.

5. Hussein ITM, et al. (2016) New England harbor seal H3N8 influenza virus retains avian-like receptor specificity. Scientific Reports 6:21428.

6. Hussein ITM, et al. (2016) A point mutation in the polymerase protein PB2 allows a reassortant H9N2 influenza isolate of wild-bird origin to replicate in human cells. Infection, Genetics and Evolution 41:279–288.

7. Holmes EC, Dudas G, Rambaut A, Andersen KG (2016) The evolution of Ebola virus: Insights from the 20132016 epidemic. Nature 538(7624):193–200.

8. Quick J, et al. (2016) Real-time, portable genome sequencing for Ebola surveillance. Nature 530(7589):228–232.

9. Loman NJ, Watson M (2015) Successful test launch for nanopore sequencing. Nature methods 12(4):303–304.

10. Jain M, et al. (2015) Improved data analysis for the MinION nanopore sequencer. Nature methods 12(4):351–U115.

11. Sovic I, et al. (2016) Fast and sensitive mapping of nanopore sequencing reads with GraphMap. Nature communications 7:11307.

12. Quick J, et al. (2015) Rapid draft sequencing and real-time nanopore sequencing in a hospital outbreak of Salmonella. Genome Biology 16(1).

13. Park DJ, et al. (2015) Ebola Virus Epidemiology, Transmission, and Evolution during Seven Months in Sierra Leone. Cell 161(7):1516–1526.

14. Dudas G, Bedford T, Lycett S, Rambaut A (2015) Reassortment between influenza B lineages and the emergence of a coadapted PB1-PB2-HA gene complex. Molecular biology and evolution 32(1):162–172.

15. Gire SK, et al. (2014) Genomic surveillance elucidates Ebola virus origin and transmission during the 2014 outbreak. Science (New York, NY) 345(6202):1369–1372.

16. Song W, et al. (2014) The K526R substitution in viral protein PB2 enhances the effects of E627K on influenza virus replication. Nature communications 5:5509.

17. Jagger BW, et al. (2010) The PB2-E627K Mutation Attenuates Viruses Containing the 2009 H1N1 Influenza Pandemic Polymerase. mBio 1(1):e00067–10–e00067–10.

18. Li J, et al. (2009) Single mutation at the amino acid position 627 of PB2 that leads to increased virulence of an H5N1 avian influenza virus during adaptation in mice can be compensated by multiple mutations at other sites of PB2. Virus research 144(1-2):123–129.

19. Paradis EG, et al. (2015) Impact of the H275Y and I223V Mutations in the Neuraminidase of the 2009 Pandemic Influenza Virus In Vitro and Evaluating Experimental Reproducibility. PloS one 10(5):e0126115.

20. Mungall BA, Xu X, Klimov A (2003) Assaying susceptibility of avian and other influenza A viruses to zanamivir: comparison of fluorescent and chemiluminescent neuraminidase assays. Avian diseases 47(3 Suppl):1141–1144.

21. Esvelt KM, Carlson JC, Liu DR (2011) A system for the continuous directed evolution of biomolecules. Nature 472(7344):499–503.

22. Ma E, Hussein ITM, Zhong V, Bandoro C, Runstadler J (2016) Bayesian Analysis of High Throughput Data. bioRxiv:079525.

23. Wang D, Larder B (2003) Enhanced prediction of lopinavir resistance from genotype by use of artificial neural networks. The Journal of infectious diseases 188(5):653–660.

24. Kjaer J, Høj L, Fox Z, Lundgren JD (2008) Prediction of phenotypic susceptibility to antiretroviral drugs using physiochemical properties of the primary enzymatic structure combined with artificial neural networks. HIV medicine 9(8):642–652.

25. Walsh I, Pollastri G, Tosatto SCE (2015) Correct machine learning on protein sequences: a peer-reviewing perspective. Briefings in Bioinformatics:bbv082.

26. Prosperi MCF, et al. (2009) Investigation of expert rule bases, logistic regression, and non-linear machine learning techniques for predicting response to antiretroviral treatment. Antiviral therapy 14(3):433–442.

27. Hepler NL, et al. (2014) IDEPI: Rapid Prediction of HIV-1 Antibody Epitopes and Other Phenotypic Features from Sequence Data Using a Flexible Machine Learning Platform. PLoS Computational Biology 10(9):e1003842.

28. Attaluri PK (2012) Classifying influenza subtypes and hosts using machine learning techniques. (ProQuest / UMI).

29. Heider D, Verheyen J, Hoffmann D (2011) Machine learning on normalized protein sequences. BMC research notes 4(1):94.

30. Check Hayden E (2016) Funding for model-organism databases in trouble. Nature.

31. Check Hayden E (2013) Popular plant database set to charge users. Nature.