Principled Git-based Workflow in Collaborative Data Science Projects

GitFlow is an incredible branching model for working with code. In this essay, I would like to introduce it to you, the data scientist, and show how it might be useful in your context, especially for working with multiple colleagues on the same project.

What GitFlow is

GitFlow is a way of working with multiple collaborators on a git repository. It originated in the software development world, and gives software developers a way of keeping new development work isolated from reviewed, documented, and stable code.

At its core, we have a "source of truth" branch called master,

from which we make branches on which development work happens.

Development work basically means new code,

added documentation,

more tests, etc.

When the new code, documentation, tests, and more are reviewed,

a pull request is made to merge the new code back into the master branch.

Usually, the act of making a branch is paired with raising an issue on an issue tracker, in which the problem and proposed solution are written down. (In other words, the deliverables are explicitly sketched out.) Merging into master is paired with a code review session, in which another colleague (or the tech lead) reviews the code to be merged, and approves (or denies) code merger based on whether the issue raised in the issue tracker has been resolved.

From my time experimenting with GitFlow at work, I think that when paired with other principled workflows that doen't directly interact with Git, can I think be of great utility to data scientists. It does, however, involve a bit of change in the common mode of working that data scientists use.

Is GitFlow still confusing for you?

If so, please check out this article on GitFlow. It includes the appropriate graphics that will make it much clearer. I felt that a detailed explanation here would be rather out of scope.

That said, nothing beats trying it out to get a feel for it, so if you're willing to pick it up, I would encourage you to find a software developer in your organization who has experience with GitFlow and ask them to guide you on it.

GitFlow in a data science project

Here is how I think GitFlow can be successfully deployed in a data science project.

Everything starts with the unit of analysis that we are trying to perform.

We start by defining the question that we are trying to answer. We then proceed forward by sketching out an analysis plan (let's call this an analysis sketch), which outlines the data sources that we need, the strategy for analyzing the data (roughly including: models we think might be relevant to the scale of the problem, the plots we think might be relevant to make, and where we think, future directions might lie).

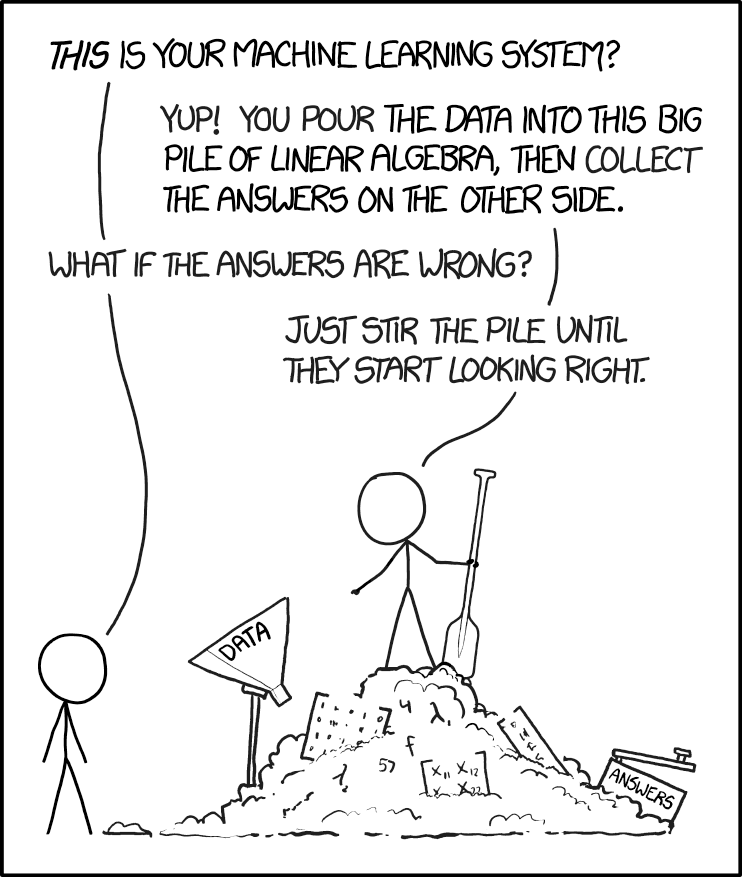

None of this is binding, which makes the analysis sketch less like a formal pre-registered analysis plan, and more like a tool to be more thoughtful of what we want to do when analyzing our data. After all, one of the myths of data science is that we can "stir the pile until the data start looking right".

About stirring the pot...

If you didn't click the URL to go to XKCD, here's the cartoon embedded below:

Once we are done with defining the analysis sketch in an issue,

we follow the rest of GitFlow-based workflow:

We create a branch off from master,

execute on our work,

and submit a pull request with everything that we have done.

We then invite a colleague to review our work, in which the colleague is explicitly checking that we have delivered on our analysis sketch, or if we have changed course, to discuss the analysis with us in a formal setting. Ideally this is done in-person, but by submitting a formal pull request, our colleague can pull down our code and check that things have been done correctly on their computer.

Code review

If you want to know more about code review, please check out another essay in this collection.

If your team has access to a Binder-like service, then review can be done in an even simpler fashion: simply create a Binder session for the colleague's fork, and explore the analyses there in a temporary session.

Once the formal review has finished

and both colleagues are on the same page with the analysis,

the analysis is merged back into the master branch, and considered done.

Both parties can now move onto the next analysis.

Mindset changes needed to make GitFlow work

In this section, I am going to describe some common mindsets that prevent successful adoption of GitFlow that data scientists might employ, and ways to adapt those mindsets to work with GitFlow.

Jumping straight into exploratory data analysis (EDA)

This is a common one that even I have done before. The refrain in our mind is, "Just give me the CSV file! I will figure something out." Famous last words, once we come to terms with the horror that we experience in looking through the data.

It seems, though, that we shouldn't be able to sketch an analysis plan for EDA, right?

I think that mode of thinking might be a tad pessimistic. What we are trying to accomplish with exploratory data analysis is to establish our own working knowledge on:

- The bounds of the data,

- The types of the data (ordinal, categorical, numeric),

- The possible definitions of a single sample in the dataset,

- Covariation between columns of data,

- Whether or not the data can answer our questions, and

- Further questions that come up while looking at the data.

Hence, a good analysis sketch to raise for exploratory data analysis would be to write a Jupyter notebook that simply documents all of the above, and then have a colleague review it.

Endless modelling experiments

This is another one of those trops that I fall into often, so I am sympathetic towards others who might do the same.

Scientists (of any type, not just data sciensists) usually come with an obsessive streak, and the way it manifests in data science is usually the quest for the best-performing model. However, in most data science settings, the goal we are trying to accomplish requires first proving out the value of our work using some form of prototype, so we cannot afford to chase performance rabbits down their hole.

One way to get around this is to think about the problem in two phases.

The first phase is model prototyping. As such, in the analysis sketch, we define a deliverable that is "a machine learning model that predicts Y from X", leaving out the performance metric for now. In other words, we are establishing a baseline model, and building out the analysis framework for evaluating how good the model is in the larger applied context.

We do this in a quick and dirty fashion, and invite a colleague to review our work to ensure that we have not made any elementary statistical errors, and that the framework is correct with respect to the applied problem that we are tackling. (See note below for more detail.)

Note: statistical errors

For example, we need to get splitting done correctly in a time series setting, which does not have i.i.d. samples, compared to most other ML problems. And in a cheminformatics setting, random splits tend to over-estimate model performance when compared to a real-world setting where new molecules are often out-of-distribution.

If we focused on getting a good model right from the get-go, we may end up missing out on elementary details such as these.

Once we are done with this, we embark on the second phase, which is model improvement. Here, we define another analysis sketch where we outline the models that we intend to try, and for which the deliverable is now a Jupyter notebook documenting the modelling experiments we tried. As usual, once we are done, we invite a colleague to review the work to make sure that we have conducted it correctly.

A key here is to define the task in as neutral and relevant terms as possible. For example, nobody can guarantee an improved model. However, we can promise a comprehensive, if not exhaustive, search through model and parameter space. We can also guarantee delivering recommendations for improvement regardless of what model performance looks like.

Note: Neutral forms of goals

As expressed on Twitter before, "the most scary scientist is one with a hypothesis to prove". A data scientist who declares that a high-performing model will be the goal is probably being delusional. I wish I knew where exactly I saw the quote, and hence will not take credit for that.

Endless ideation prototyping

Another trap I have fallen into involves endless ideation prototyping, which is very similar to the "endless modelling experiments" problem described above.

My proposal here, then, is two-fold. Firstly, rather than running down rabbit holes endlessly, we trust our instincts in evaluating the maturity of an idea. Secondly, we ought also to define "kill/stop criteria" ahead-of-time, and move as quickly as possible to kill the idea while also documenting it in a Jupyter notebook. If made part of an analysis sketch that is raised on the issue tracker, then we can be kept accountable by our colleagues.

Benefits of adopting GitFlow and associated practices

At its core, adopting a workflow as described above is really about intentionally slowing down our work a little bit so that we are more thoughtful about the work we want to finish. In work with my colleagues, I have found this to be incredibly useful. GitFlow and its associated practices bring a suite of benefits to our projects, and I think it is easy to see how.

By spending a bit more time on thought and on execution, we cut down on wasted hours exploring unproductive analysis avenues.

By pre-defining deliverables expressed in a neutral form, we reduce stress and pressure on data scientists, We also prevent endless rabbit-hole hacking to achieve those non-neutrally-expressed goals. We also receive a less biased analysis, which I believe can only help with making better decisions.

Finally, by inviting colleagues to review our work, we also prevent the silo-ing of knowledge on one person, and instead distribute expertise and knowledge.

How to gradually adopt GitFlow in your data science teams

I know that not every single data science team will have adopted GitFlow from the get-go, and so there will have to be some form of ramp-up to get it going productively.

Because this is a collaborative workflow,

and because adoption is usually done only in the presence of incentives,

I think that in order for GitFlow and associated practices to be adopted,

one or more champions for using GitFlow needs to be empowered

with the authority to use this workflow on any project they embark on.

They also have to be sufficiently unpressured to deliver,

so that time and performance pressures do not compromise on adoption.

Finally, they have to be able to teach git newcomers

and debug problems that show up in git branching,

and be able to handle the git workflow

for colleagues who might not have the time to pick it up.

Tooling also has to be present. A modern version control system and associated hosting software, such as BitBucket, GitHub and GitLab, are necessary. Issue trackers also need to be present for each repository (or project, more generally).

At my workplace, I have been fortunate to initiate two projects on which we practice GitFlow, bringing along an intern and a colleague one rank above me who were willing to try this out. This has led to much better sharing of the coding and knowledge load, and has also allowed us to cover for one another much more effectively.

While above I may have sounded as if there is resistance to adoption, in practice I know that most data scientists instinctively know that proper workflows are going to be highly beneficial, but lack the time/space and incentives to introduce them in, yet would jump at the chance to do so if properly incentivized and given the time and space to do so.

Concluding words

I hope that I have convinced you that learning GitFlow, and its associated practices, can be incredibly useful for the long-term health and productivity of your data science team(s).