Eric J Ma's Website

written by Eric J. Ma on 2025-12-02 | tags: statistics biotech reproducibility experiments research automation ai data open source bayesian

In this blog post, I share my journey building a domain-specific statistics agent to help researchers design better experiments, inspired by the challenges of limited access to statisticians in pharma and biotech. I discuss the pitfalls of "folk statistics," the importance of prompt engineering, and the lessons learned through iterative testing and refinement. Curious how an AI agent can elevate experimental design and what it takes to make it truly helpful?

Within research organizations at most pharma and biotech companies, professionally-trained statisticians are often staffed at extremely low ratios relative to the number of lab scientists. By rough Fermi estimation, I'd hazard a guess that ratios anywhere from 1:10 to 1:100 are plausible, meaning most researchers have limited access to statistical expertise when they need it most, during experiment design. This statistician shortage creates a critical bottleneck in experimental design, power calculations, and biostatistical consultation—areas where proper statistical guidance can prevent costly mistakes and improve research reproducibility.

This creates a costly problem. When statisticians aren't available, researchers fall back to what I call "folk statistics" - the kind you learn by immersion in a lab, or from 1-2 graduate lectures hidden within broader "laboratory methods" or "computational methods" classes. I know this because I practiced folk statistics myself in the life sciences, blindly following rules like "just do n=3" or "just use the t-test with your count data" without understanding the statistical reasoning behind these choices.

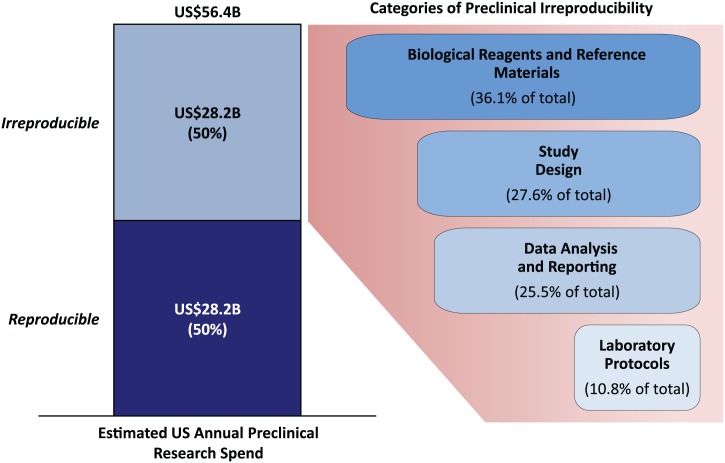

The consequences are documented in stark numbers. Amgen scientists attempted to reproduce 53 landmark preclinical papers and failed in 47 cases (89%)—even after contacting original authors and exchanging reagents. Bayer's internal validation found only 20-25% of studies "completely in line" with original publications. These studies consistently identified poor experimental design and inadequate statistical analysis as major contributors. Freedman et al. (2015) estimated $28 billion annually spent on irreproducible preclinical research in the United States alone.

Breakdown of causes of preclinical irreproducibility from Freedman et al. (2015). Study design accounts for 27.6% of irreproducibility.

At the individual experiment level, this translates to teams throwing out hard-won experimental data that can cost anywhere from thousands to hundreds of thousands of dollars to collect per round, wasting up to millions of dollars downstream by basing decisions on poorly-collected data, and missing opportunities to set up machine learners with high quality laboratory data that could shortcut the amount of laboratory experimentation needed.

I took one semester of graduate-level biostatistics, then a decade of self-study in Bayesian statistics, followed by professional work where accurate estimation was critical—whether estimating half-life of a molecule, binding affinity of an antibody, or other performance properties. Through this journey, I no longer trust folk statistics. Folk statistics relies on faulty assumptions—like "n=3 is all you'll really need," "use the t-test for count data," or "calculate the SEM and don't show the SD"—which influence bad decision-making when people don't know better. Once you see how these assumptions break down and lead to wrong conclusions, you can't unsee it. Quantities like half-life, binding affinity, and other performance properties need to be accurately estimated through proper experimental design and statistically-informed mechanistic modeling.

Statisticians are expensive, but they're also 100% critical for generating high quality, high fidelity data. Their role at the experiment design phase is usually that of a consultant, asking probing questions to ensure experiments are designed with good controls, confounders are accounted for, and the right statistical models are chosen. The question is: can we scale this expertise?

Not to replace statisticians, but to level up the organizational statistical practice before researchers check in with a professionally-trained stats person. If lab scientists can think through their experimental designs more rigorously beforehand - understanding power calculations, considering confounders, planning proper controls - then the conversations they have with statisticians can be elevated. Instead of starting from scratch, they can engage in more sophisticated discussions about design trade-offs, model selection, and advanced statistical considerations. In turn, this amplifies the value of the statistician's time and improves outcomes for everyone.

I was inspired by Dr. Emi Tanaka's slides on extracting elements of statistical experiment design using LLMs, which showed how we can extract structured information like response variables, treatments, experimental units, design types, replicate structure, and controls. I decided to take a stab at building something that could do more than just extract information—something that could actually consult on experiment design.

And so stats-agents was born: an AI-powered statistics agent for experiment design consultation. Here's how I designed and evaluated this domain-specific AI agent.

As a preface, I initially explored the ReAct pattern but switched to PocketFlow, a minimalist graph-based framework that replaced 307 lines of agent orchestration code with just 4 lines. This graph-based approach brought clarity, modularity, and made the execution flow explicit—exactly what I needed for building a robust statistics agent.

So how did I go about building this agent?

Deeply influenced by Clayton Christensen's books, I actually started with "what's the job for this agent to be done?" I initially considered building a single agent that could handle both experiment design consultation and statistical analysis of collected data. However, I quickly realized these are fundamentally different phases with different goals, tools, and interaction patterns.

The experiment design phase is consultative and exploratory - it's about asking questions, understanding constraints, identifying potential issues, and helping researchers think through their design before data collection. The analysis phase is more technical - it's about taking collected data and building statistical models to estimate quantities of interest.

I decided to focus the agent on the design phase only. This separation of concerns made the agent cleaner, less confusing, and allowed it to be optimized for its specific purpose: being an inquisitive, consultative partner during experiment design. The analysis phase would be handled separately (or by a different agent) with its own tools and prompting strategies.

So I defined the agent's job description (JD) as: "an agent that will provide critique on experiment designs, suggest modifications, and help researchers think through their experimental design before data collection". It sounded oddly like a human's job description for a real job, except more specific. Notice, however, that the JD leaves room for a real human, in that no accountability for outcomes is placed on the agent, a human statistician still needs to review the work, just as we wrote above.

With the job scope defined, I turned to designing the tools the agent would need.

The first tool I gave was critique_experiment_design - a tool that provides comprehensive critique of experiment designs, identifying potential flaws, biases, weaknesses, and areas for improvement. This tool considers multiple angles including biological, statistical, and practical constraints. The agent can use this to help researchers identify issues in their designs before they collect data.

The second tool I gave was one I previously wrote about: the ability to execute code (write_and_execute_code). I wanted this available to answer questions like "what should my data table look like?"

I've noticed that having a sample data table in front of us when discussing experimental designs is incredibly clarifying—it cuts through abstract confusion toward concrete understanding. This tool enables the agent to generate sample data tables, perform power calculations, create plate map visualizations, and other dynamic analyses.

Important security note: The ability to execute arbitrary Python code is powerful but also dangerous. An agent that can execute code can delete files, modify system configurations, access sensitive data, make network requests, and more. For any production deployment, this agent must run in a containerized environment with strict isolation, resource limits, and no access to secrets or credentials. This isn't optional - it's a cybersecurity requirement! For my development and testing, I ran it in a controlled environment on my own machine, but production deployment would require proper containerization.

With the tools defined, the next challenge was evaluation: how do you know if the agent is actually working? This turned out to be more complex than I initially expected.

The evaluation process had two distinct phases: an exploration-guided MVP phase (vibes-driven) and a post-MVP systematic testing phase.

Phase 1: MVP Development (Vibes-Driven)

During the MVP phase, I defined a fixed conversation path and repeatedly tested it manually in a Marimo notebook's chat UI. I tested with a sequence like: asking for design critique, providing an experiment description, requesting power calculations, and asking for sample data tables. As I found errors, I fixed them immediately, contrary to evaluation best practices, but appropriate for this exploratory phase. The tool definitions weren't settled until this phase was complete.

I also used Cursor (a coding agent) to help diagnose issues, explore multiple solutions, and get different perspectives before committing to fixes. This "multiple AI opinions before committing" pattern follows a similar philosophy to Geoffrey Litt's "Code like a surgeon" approach: spike out an attempt at a big change, review it as a sketch of where to go, and often you won't use the result directly—but it helps you understand the problem space better.

Rather than accepting the first AI suggestion, I'd ask multiple questions, explore several solution approaches, and understand the trade-offs before making an informed decision. When debugging complex issues like the closure vs. shared state problem, I'd often ask multiple models the same question to see if they'd converge on the same diagnosis—if different LLMs independently arrived at the same answer, that was a good sign the solution was on the right track. This led to better architecture decisions and fewer instances of "I wish I had done it differently."

Phase 2: Systematic Evaluation

Once the baseline behavior was satisfactory, I moved to systematic evaluation.

Benchmark prompt: I created a "perfect prompt" document (experiment_design_for_power_calc.md) that served as my regression test suite. This complete, detailed experiment design specification should trigger specific agent behaviors, such as asking the right questions, performing power calculations correctly, providing contextual explanations. Every time I modified the system prompt or tools, I'd run this same benchmark and check: did it still work? Without this, I found myself making changes that broke things in subtle ways, or losing track of what "good" behavior even looked like. The benchmark prompt became my north star, a concrete example of the agent working as intended.

Synthetic test generation: Once I had a reliable benchmark, I expanded to systematic evaluation with variation. Starting with five examples from Tanaka's slide deck, I used the methodology from Shreya Shankar and Hamel Husain (researchers who developed systematic approaches for LLM evaluation) to generate synthetic chat examples by selecting 1-3 axes of variation. I chose experimental domain (biotech vs. agriculture) as the primary axis, while varying the statistical expertise level of the simulated user. This process generated dozens of conversation traces that, while not exhaustive, represented draws from my constrained prior belief about likely conversations.

Systematic evaluation with these varied conversation traces revealed patterns I never would have noticed through manual testing. Through these traces, I identified three major categories of failure modes that needed to be addressed.

Failure mode 1: Multi-step execution breakdown

The first major issue I encountered was that the agent couldn't chain tool calls effectively. When the agent executed code to perform a power calculation, it would store the result in a variable like mtt_power_analysis_result. But when it tried to analyze that result in a subsequent tool call, it would fail with a NameError - the variable simply wasn't accessible.

The root cause was subtle: the code execution tool (write_and_execute_code_wrapper) was using a closure variable that captured the notebook's globals at initialization time. However, the agent framework (AgentBot) stores results in a separate shared dictionary (shared["globals_dict"]). These two dictionaries were disconnected; think of them as two separate notebooks that couldn't see each other's variables. So when the agent created a variable in one tool call, it wasn't visible to the next.

The fix required connecting them: I modified the code execution tool to accept an optional _globals_dict parameter. When provided, it uses the agent's shared dictionary instead of its own isolated one. This allows results from one tool call to be accessible in subsequent calls, enabling true multi-step workflows where the agent can build on previous results.

Failure mode 2: Display formatting and contextual output

The second category of issues involved both technical display problems and behavioral output quality. When the agent returned Python objects (DataFrames, matplotlib figures, etc.), they weren't displaying properly in the Marimo chat interface. The agent would return a dictionary with these objects, but Marimo's chat UI doesn't automatically render matplotlib Figure objects embedded in dictionaries.

But there was a deeper behavioral problem: the agent was dumping DataFrames and plots without any explanatory text. I'd ask for a power analysis, and the agent would return a raw DataFrame with numbers -- no context, no interpretation, no explanation of what I was looking at. My sense of taste rebelled. This wasn't just a technical problem, it was an aesthetic one. I wanted a polished, consultant-like experience where explanatory text naturally flows between objects, not a data dump.

Sometimes the best technical solutions come from caring about how things look and feel.

I solved both problems through a combination of technical infrastructure and prompt engineering. With AI assistance, I created a formatter system that processes dictionaries containing text and objects, converting strings to markdown and passing objects through for native display. This handled the technical display issue. It's implemented within llamabot/components/formatters.py as create_marimo_formatter.

But to solve the behavioral problem—getting the agent to actually provide contextual text—I had to update the system prompt. I added explicit guidance requiring that every object be preceded (and ideally followed) by explanatory text that connects back to the researcher's goals. The prompt now instructs the agent to create a dictionary with explanatory text strings interleaved with objects, then return it. The formatter processes this dictionary, creating that polished, consultant-like experience where text naturally flows between objects.

Failure mode 3: Agent decision-making and domain knowledge

The third category of failures involved the agent's decision-making process and understanding of domain conventions. Through systematic evaluation, I discovered several patterns.

Here's a concrete example of how the prompt evolved. Initially, I had a simple instruction: "Ask clarifying questions about experiment goals, constraints, and assumptions." But the agent kept jumping straight to calculations. So I added:

Before (early version):

Ask clarifying questions about experiment goals, constraints, and assumptions.

After (refined version):

CRITICAL - BE INQUISITIVE FIRST: Before jumping into calculations, you MUST ask probing questions to understand the full context:

- What effect size are they expecting or hoping to detect? Why?

- What is the expected variability in their measurements? Do they have pilot data?

- What are their practical constraints (budget, time, sample availability)?

- What are they most worried about with this experiment?

- Have they done similar experiments before? What issues did they encounter?

- What would make this experiment a "success" in their view?

Only after gathering this context should you use

write_and_execute_code_wrapperto perform calculations.

The agent wasn't inquisitive enough. Despite the system prompt emphasizing the need to ask questions, the agent would often jump straight to calculations without first understanding the researcher's context, constraints, and goals. I had to add multiple "CRITICAL" reminders in the prompt, explicitly stating that questioning should happen BEFORE calculations.

The agent was trying to pass variable names as strings. When the agent wanted to analyze a result from a previous tool call, it would try to write a function like def analyze(mtt_power_analysis_result): and pass {"mtt_power_analysis_result": "mtt_power_analysis_result"} - which passes the string literal, not the actual dictionary! I had to explicitly teach the agent to write functions with NO parameters that access variables directly from globals.

Contradictions in the system prompt. There were conflicting instructions about when to use respond_to_user vs return_object_to_user. I resolved this by clarifying: use respond_to_user for text-only responses, and return_object_to_user when you have Python objects to display.

The agent didn't understand domain-specific visualizations. When the test user (a.k.a. me) asked for a "plate map" or "plate layout visualization," the agent would generate something, but it often wasn't what researchers expected.

A plate map visualization in experimental biology is a very specific thing: a heatmap-style 8×12 grid (rows A-H, columns 1-12) where each well is color-coded by treatment group with a clear legend. Without explicit guidance, the agent would create generic bar charts or scatter plots that didn't match these domain conventions.

I solved this by adding detailed specifications in the system prompt that describe exactly what plate map visualizations should look like, including the grid structure (rows labeled A-H, columns 1-12 for 96-well plates), color coding requirements (different colors per treatment, with a legend), complete code patterns showing how to create them with matplotlib, common plate formats (96-well, 384-well, 1536-well), and trigger phrases that should generate plate maps.

This pattern - providing detailed specifications for domain-specific outputs - became a key strategy. When the agent needs to generate something that follows domain conventions, it needs explicit guidance on what those conventions are.

Addressing these behavioral issues required multiple rounds of iteration. The system prompt didn't reach its final form in one go - as I discovered each issue, I added more explicit guidance, examples, and "CRITICAL" warnings. The prompt grew substantially through iterative refinement, and the agent's behavior improved dramatically with each iteration.

The process wasn't linear during the early iteration phases - I'd fix one issue, test it, discover another, fix that, and sometimes realize the first fix needed refinement. Working with the Cursor coding agent helped me identify contradictions, explore multiple solution approaches, and get different perspectives before committing to changes. This iterative refinement process is essential when building domain-specific agents: you can't anticipate all the behavioral issues upfront, so you need to be prepared to evolve the prompt based on what you discover through testing.

Conclusion: Key lessons for building domain-specific agents

Building this AI statistics agent for experiment design revealed several important patterns that apply broadly to building domain-specific AI agents and LLM-powered tools:

1. The system prompt is the primary control surface

The agent's personality, decision-making process, inquisitiveness, and ability to provide contextual explanations are primarily controlled through prompt design rather than code changes. The prompt is where the domain knowledge lives, where the behavioral patterns are encoded, and where the "personality" of the agent is defined. Code provides the infrastructure, but the prompt provides the intelligence.

If you want to change the agent's behavior, you're often better off modifying the prompt than changing the code. The prompt became a detailed instruction manual that teaches the agent not just what to do, but how to think, when to ask questions, and why certain patterns matter.

2. Testing is essential, but not sufficient

Even with extensive testing, you cannot guarantee what will be seen in the real world. Users will ask questions you never thought of, use terminology you didn't anticipate, have edge cases in their data you didn't consider, and interact with the agent in ways that break your assumptions.

This is why the agent is designed as a consultant rather than an autonomous decision-maker. A human statistician still needs to review the work. The testing process is essential for building confidence, but you must also design the system with the assumption that it will encounter unexpected situations. This means implementing clear error handling, graceful degradation when things go wrong, explicit boundaries on what the agent can and cannot do, and human oversight for critical decisions.

Final thoughts

The process of building this agent revealed something I didn't expect: you can't anticipate all the behavioral issues upfront. The prompt grew from ~200 to ~600 lines through iterative discovery—each failure mode required explicit guidance I didn't know I'd need. Building domain-specific agents means being prepared to evolve your approach based on what you discover through testing, not just what you plan in advance.

Try it yourself

The experiment design agent is available as a Marimo notebook in the LlamaBot repository. You can run it locally with:

git clone git@github.com:ericmjl/llamabot.git cd llamabot/notebooks uvx marimo edit --watch notebooks/experiment_design_agent.py

The agent is designed to be inquisitive and consultative—it will ask probing questions about your experiment goals, constraints, and assumptions before providing recommendations. This AI statistics agent can help with power calculations, experimental design critique, sample data table generation, plate map visualizations, and biostatistical consultation for researchers in pharma and biotech.

Limitations: This agent is a prototype focused on the experiment design phase. It's not a replacement for human statisticians—it's designed to amplify their knowledge and help researchers think through their designs before data collection. The agent requires human oversight and review, especially for high-stakes decisions. I haven't tested it across all experimental design types, and it may struggle with highly specialized domains or unusual constraints.

If you're interested in building your own domain-specific agent, I hope the lessons and patterns shared here provide a useful starting point. The code is open source, and I welcome contributions and feedback.

I'm working on a part 2 of this blog post, where I'll build out the statistical analysis agent—the companion to this experiment design agent. That post will cover how to build an agent that takes collected data and performs statistical analysis, model fitting, and interpretation.

Thank you for reading this far. If you made it here, you've invested real time and attention in understanding not just what I built, but how and why—and that means a lot! Building this agent has been four months in the making, and sharing those discoveries with others who care about the same problems is what makes the work worthwhile. I'm grateful you came along for the ride!

Cite this blog post:

@article{

ericmjl-2025-what-does-it-take-to-build-a-statistics-agent,

author = {Eric J. Ma},

title = {What does it take to build a statistics agent?},

year = {2025},

month = {12},

day = {02},

howpublished = {\url{https://ericmjl.github.io}},

journal = {Eric J. Ma's Blog},

url = {https://ericmjl.github.io/blog/2025/12/2/what-does-it-take-to-build-a-statistics-agent},

}

I send out a newsletter with tips and tools for data scientists. Come check it out at Substack.

If you would like to sponsor the coffee that goes into making my posts, please consider GitHub Sponsors!

Finally, I do free 30-minute GenAI strategy calls for teams that are looking to leverage GenAI for maximum impact. Consider booking a call on Calendly if you're interested!